By 1910, L. Frank Baum had become exhausted with his popular Oz series, going so far as to announce that the citizens of Oz had conveniently chosen to cut themselves entirely off from the rest of the world, ending the Oz tales.

But Baum still had to make a living, so, like many a professional author, he studied his previous works to see what, besides Oz, might bring in some cash. He was astute enough to realize one noticeable difference between his Oz bestsellers and most of the rest of his books: the bestsellers featured young Americans traveling to fairylands. And so, Baum decided to try a slight twist on his Oz formula, with a tale about a young girl traveling to a fairyland—but not alone, and not to Oz.

Sea Fairies opens on a foreboding note, as Cap’n Bill tells young Trot that no one has ever seen a mermaid and lived to tell the tale. Trot points out the illogic of this statement—in that case, how do we even know mermaids exist?—and announces that she wants to see a mermaid anyway, whatever the danger. As it happens, a group of mermaids just happen to overhear this wish (some people have all the luck)—and decide to grant it.

Over Cap’n Bill’s objections, the mermaids transform the two humans into water fairies and lead them to the kingdoms beneath the sea. (Even in fantasy, Baum had not lost his scientific touch: both Trot and Cap’n Bill take a moment to wonder why the water pressure isn’t crushing them before concluding that magic will defeat science every time, at least for those fortunate enough to be traveling with fairies.

Baum had clearly done a bit of research into real underwater realms and coral reefs. The sea chapters are filled with names and descriptions of real fish and coral, interspersed with the inevitable jokes and puns. Some of these—particularly the one comparing the Standard Oil Company to an evil octopus, and the holy mackerels—are still funny. But alas, much of this touring the bottom of the seas section now feels quite dated, since many of the jokes have lapsed into complete obscurity. For that matter, I’m not sure how many of Baum’s contemporaries would have gotten the Boston codfish aristocracy joke.

Fortunately, the story starts revving up again when the tourists find themselves captured by the great and terrible Zog the Forsaken, who wants to kill Trot and her companions as part of his revenge on Anko, a sea serpent he hates. If this seems a little complicated to you, you may not be an evil mastermind. Zog has two problems: he needs to figure out how to kill the mortals in a very painful way, and how to kill the immortal mermaids at all. Trot and Cap’n Bill assure Zog that they’re in no hurry.

Zog is a bit different than many of Baum’s other villains, who tend to be evil because they are evil. Zog is evil because he is frustrated and bored. His inability to take direct revenge on his enemy and his feelings of entrapment in his underwater palace have turned him actively sadistic. His attempts to kill Trot and her companions are intended to cause both terror and pain.

But Baum does not slide into the simplistic argument that Zog became evil through evil circumstances, providing a counterexample in Zog’s human slave Sacho. Like Zog, Sacho has every reason to turn bitter and evil. Not only is he regularly exposed to his master’s evil, but like Zog, Sacho is also trapped in the underwater palace, not because of anything he has done, but because of a shipwreck. And yet, Sacho remains cheerful and nonchalant, not even hating Zog, who has enslaved him. He explains his philosophy in a few brief sentences:

“But you’re wasting time hating anything. It doesn’t do you any good, or him any harm. Can you sing?”

“A little,” said Trot, “but I don’t feel like singing now.”

“You’re wrong about that,” the boy asserted. “Anything that keeps you from singing is foolishness, unless it’s laughter. Laughter, joy and song are the only good things in the world.”

It’s one way to respond to helpless slavery, I suppose, although my guess is that Zog’s more bitter response is more typical.

The tourists encounter another important person in Zog’s palace: Cap’n Bill’s long lost brother, Cap’n Joe, who, like Cap’n Bill, sports a wooden leg, and who, unlike Cap’n Bill, now has gills. And while Cap’n Bill’s wooden leg causes him little trouble on land, Cap’n Joe has the opposite problem at the bottom of the sea: the leg wants to float, making it difficult for Cap’n Joe to stomp around. This leads to all sorts of awkward questions (mostly around how exactly they are all standing upright and walking around in the first place, and why they aren’t just swimming), but it’s also one of the few cases in Baum’s works of a disability causing stressful and problematic mobility problems.

Even with this, however, neither character falls into the standard disability tropes so prevalent in the literature of the time (and still around today): they are characters who happen to be disabled, rather than characters defined by their disabilities.

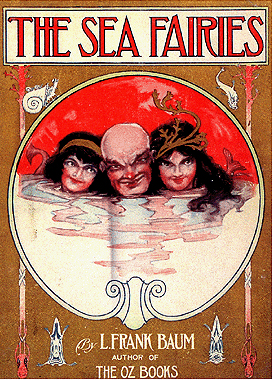

Sea Fairies is an uneven book, which perhaps explains why sales were disappointing. But it serves to introduce two of Baum’s most important characters: Trot and Cap’n Bill, who would take center stage in three more books (two of them set in Oz.) And it gave Baum the chance to enjoy his wordplay and puns in a setting that was not Oz, an experience he enjoyed so much that he was immediately willing to try it again.

Mari Ness regretfully reports that she has never met any talking fish in the coral reefs she’s explored around Florida. Perhaps they’ve decided to stop talking to tourists.